Suzy Phillips Anderle of Sun City was seven months old in September, 1944, when her father, Joseph L. Phillips, was killed in action in World War II. For the past year, she has worked to enhance his legacy of service with her own historical research and travels. On this Veterans Day of 2014, this is her story:

Joe Phillips had his future planned out in September 1944, despite the turmoil of war and conflict throughout the world, and World War II raging throughout Europe.

Things were going well for him, he thought, as he boarded a glider that would carry him into battle in a few hours. Married two years before and with the memory of recently seeing his three-week-old daughter, dancing happily in his head, he felt he had a right to believe he would survive the terror of war. He had survived action on D-Day and its aftermath in Normandy’s hedgerows.

Suzy Phillips Anderle at the cemetery where her father, First Lt. Joseph L. Phillips, was buried in 1944-45. (Photos provided)

He was doing something important for his family, his friends, and his country. He was planning to stay in the army after the war ended. He was pursuing a cause as well as a career.

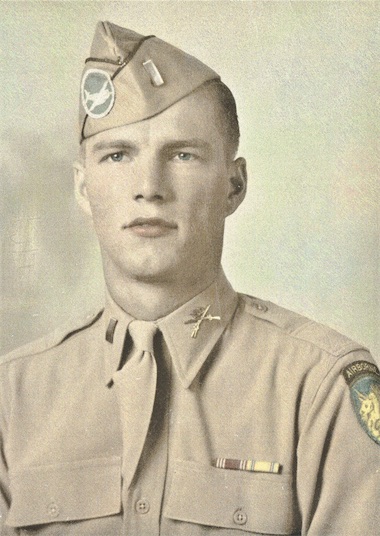

First Lt. Joseph L. Phillips.

Joe and 13 of his buddies in the 327th Glider Infantry regiment were part of the 101st Airborne Division, which was in the the process of becoming one of America’s most famous and successful fighting units. Their WACO CG-4A glider was towed by a C-47 transport in Operation Market Garden, which today remains the largest airborne assault ever mounted. About 20,000 American and British paratroopers and glider-based infantrymen landed behind enemy lines in the Netherlands in an attack designed to shorten the war and open a path into Germany . British and American military leaders said this operation could bring the war to an end by Christmas. The assault failed and the war lasted until May 1945.

Their glider flew over northern Belgium on its way to its landing zone near Eindhoven, Netherlands. Joe, as a First Lieutenant and the highest ranking officer, was sitting in the co-pilot’s seat, because the glider units were short of pilots. His job was to try and fly the glider if anything happened to the pilot.

Their transport and glider came under heavy enemy anti-aircraft fire. The C-47 was hit first, and suddenly a blast of flak struck the WACO on the co-pilot’s side, killing Phillips instantly. The towline connecting the glider to the transport then parted, evidently struck by a German shell. Pilot Darlyle Watters, slightly wounded, was on his own and far off his intended course. With one of the 15 men dead and two wounded, he managed to land the damaged glider in a drainage ditch near a small Belgian town. The 12 survivors were captured a few minutes after landing and spent the final eight months of the war in a German prison camp.

On Oct. 15, three weeks later, Joe’s wife, Dorothy, received a telegram that her husband was missing. Six weeks later, she was notified that his death was confirmed.

Many relatives of fallen soldiers have taken the opportunity to relive their loved ones’ experiences by traveling to the locations where the incidents happened. The visits are bittersweet, full of both heart-wrenching and heart-warming experiences. Suzy and her husband Harry had such an experience last month.

“I decided in the 90s that I wanted to find out all I could about my father’s death, and it intensified this year,” Suzy said as she showed this Sun Day reporter an inch-thick file of documents that she has found and collected since 1996. “That year, I heard from a friend that you could apply for an Individual Deceased Personnel File (IDPF), if you were a relative of the deceased person. It took almost a year, but I received a 90-page file from the government that provided a lot of details about my father that I had not known before. I knew from my mother that the Germans turned his body over to local townspeople, and he was buried in a small municipal cemetery in Retie, Belgium, a few miles from the border with Holland. Twenty-one American servicemen were buried in the town, all in a row. Townspeople obtained the names and service numbers, probably from dogtags on the bodies, and put up wooden plaques by each coffin, identifying each one.

“After the war ended, thousands of allied soldiers roamed all over Europe, finding, identifying, and burying bodies of American servicemen in military cemeteries all over the continent. Joe’s body was transferred from Retie to Liege, a large city in Belgium in June 1945. Four years later, at the request of my grandmother, his body was returned to Rhinelander, Wisconsin, where Joe was born and raised, and buried there with military honors in 1949. The government paid all of the expenses of taking his body from Belgium by train, ship, and then train again to our family home town. A serving veteran escorted the body on the train from the east coast to St. Joseph Cemetery in Rhinelander.

“Harry and I both grew up in Rhinelander, were high school sweethearts, and we have lived in Wisconsin all of our lives until we came to Sun City nine years ago.”

While Suzy continued her research on World War II and her father’s activities, she and Harry planned to travel to Paris and Normandy this fall on a tour sponsored by Holiday Vacations of Eau Claire, Wisconsin.

“Harry’s sister, Ginger, encouraged us to go,” Suzy recalled, “and Harry suggested that, since we were going to be in Paris, we could rent a car and drive to Retie and Liege and actually see the places where my dad served and died.”

Suzy and Harry toured the beaches, cemeteries and museums of Normandy, visited Paris, and then drove to Retie, where their visit turned into a celebration.

“We were met by a group of citizens and officials of the town, which now has about 10,000 people,” Suzy said. “They took us to the cemetery where he was buried for eight months. Only one soldier remains there, the rest were all moved. They told me I could start at the last remaining grave, walk 15 paces away, and I would stand on the spot where my father was buried for eight months. It was so emotional and yet so inspirational. Harry took a picture of me laying a flower on top of a hedge next to the location of his grave. It’s hard to describe your feelings at such a moment.”

They met the Retie mayor, were honored by local residents at a dinner, and enjoyed three days of wonderful hospitality in Retie.

“The people there just love Americans, who liberated them in the war,” Suzy said. “They really enjoyed having us come and renew memories. They call their cemetery ‘hallowed ground.’ We met Marie Van Gestel, a librarian and historian in Retie, who told us so many interesting things about their area’s history.

“I earlier had received a whistle my father carried with him on the flight. I gave it back to the Retie people as a thank you for their efforts. I have his canteen, his Purple Heart, and the last letter he wrote to my mom, dated Sept. 16, 1944, three days before he died. It has been so wonderful to be able to find all of this information and meet so many people who have been so helpful,” Suzy concluded. “I feel like I could write a book about it all. This last year has been one of the best years of my life.”

21 Comments

To the mysundaynews.com webmaster, Your posts are always a great source of knowledge.

Hi mysundaynews.com webmaster, You always provide great insights.

Hi mysundaynews.com admin, Your posts are always well received by the community.

Dear mysundaynews.com administrator, You always provide practical solutions and recommendations.

Dear mysundaynews.com admin, Keep up the good work!

Hello mysundaynews.com admin, Your posts are always well-delivered and engaging.

Hello mysundaynews.com webmaster, Your posts are always informative and well-explained.

To the mysundaynews.com webmaster, You always provide great examples and real-world applications, thank you for your valuable contributions.

Dear mysundaynews.com admin, Thanks for the well-organized and comprehensive post!

Hello mysundaynews.com admin, You always provide great examples and real-world applications, thank you for your valuable contributions.

Hello mysundaynews.com webmaster, Good to see your posts!

Hi mysundaynews.com webmaster, Your posts are always well-referenced and credible.

To the mysundaynews.com webmaster, Your posts are always informative and well-explained.

Dear mysundaynews.com webmaster, Thanks for the great post!

Hi mysundaynews.com owner, Your posts are always well-supported by research and data.

To the mysundaynews.com admin, Great post!

To the mysundaynews.com administrator, You always provide practical solutions and recommendations.

Hello mysundaynews.com administrator, Your posts are always well-supported by facts and figures.

Dear mysundaynews.com admin, Your posts are always well-cited and reliable.

To the mysundaynews.com administrator, You always provide useful links and resources.

To the mysundaynews.com administrator, Your posts are always well thought out.